Band of Brothers

WWII Mini-Series Portrays Local Retiree

Snow drifts softly through the trees, dusting the soldiers’ uniforms as they move forward, their M-1s, carbines, and Tommy guns at the ready.

Then 1st Sgt. Carwood Lipton speaks, his tone indifferent yet determined, revealing, finally, that these are the desperate days of World War II, and that Easy Company, battle-weary but unbroken, has been holding the line around Bastogne for more than a month.

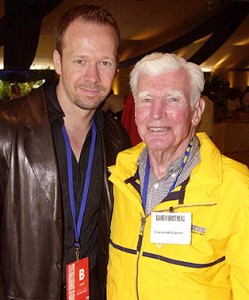

“That’s me speaking on the voice-over,” says the real Carwood Lipton, now a Southern Pines retiree, as he watches the DreamWorks HBO video. “Or that’s supposed to be me. It’s really Donny Wahlberg playing me back then. But they’ve done a pretty good job. We would have attacked just that way – spread out so that we were ready to hit the ground if we were fired on.”

As Lipton watches a rough cut of Episode 7 of the 10-part mini-series “Band of Brothers,” which is scheduled to begin airing on HBO in September, he remembers the cold, the privation, and the death. But he also recalls the camaraderie, the sense of belonging. All of it comes home now, the handiwork of the finest writers, directors, and actors in the movie business.

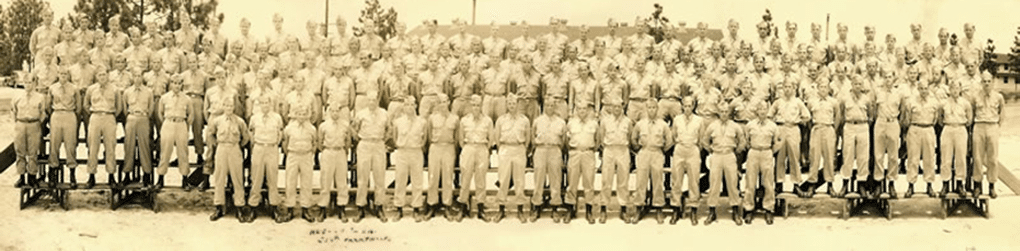

Carwood Lipton was, and always will be, a member of Easy Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne, the legendary unit that fought its way from Normandy to Hitler’s fortified Eagle’s Nest retreat at Berchtesgaden, Bavaria. The unit received national attention in 1992 when Stephen Ambrose’s nonfiction book “Band of Brothers” was riding high on the bestseller list.

Most Ambitious TV Movie Ever

The cinematic retelling of Easy Company’s story — which has thus far cost an estimated $200 million — is the most expensive and most ambitious movie ever made for TV. Tom Hanks, the star of “Saving Private Ryan,” is directing and producing, along with Steven Spielberg. The movie has employed a cast of 500 speaking actors and 10,000 extras. In the service of authenticity, entire villages, entire warscapes have been meticulously recreated on a backlot in England, the same lot where “Saving Private Ryan” was filmed.

But the story of Easy Company is broader in scope than “Saving Private Ryan,” following the 101st paratroopers from their rigorous training in Georgia through their battles in Normandy, Holland, Belgium and Germany. And Carwood Lipton is one of the few paratroopers who remained a member of Easy Company from Georgia to Bavaria.

But the story of Easy Company is broader in scope than “Saving Private Ryan,” following the 101st paratroopers from their rigorous training in Georgia through their battles in Normandy, Holland, Belgium and Germany. And Carwood Lipton is one of the few paratroopers who remained a member of Easy Company from Georgia to Bavaria.

“I saw a lot of combat during the war,” says Lipton. “I lost a lot of friends. The fighting around Bastogne was bad because it went on for so long, but I think I was most frightened in Normandy on D-Day when we were attacking the 105s that were shelling Utah Beach.”

After flanking the German position and firing on the defenders while balancing in a small tree, Lipton was crawling back to get TNT and percussion caps to destroy the German guns when a friend, Warrant Officer Hill, was killed by enemy fire.

“There was German fire right over us,” Lipton says. “Hill asked where battalion headquarters was. The officer in front of me yelled that it was back on the road. Hill raise his head – just 8 or 10 inches – and a bullet hit him right in the forehead. I was looking straight at him. The bullet entered his forehead and came out the back of his head, killing him instantly.

“Except that the body doesn’t die instantly. The body jerks and snorts and twists, and that shook me up. The machine gun fire was cracking right over us, and I was sure they were going to get me too. Hill was the first American I saw hit. I’d seen dead American bodies, but I knew Warrant Officer Hill very well. I managed to get out, but that was the time I was probably most afraid.”

Unit Was Left Stranded

After recovering from wounds received in Normandy, Lipton participated in operation Market-Garden, the Allies’ abortive invasion of Holland. British paratroopers took the bridge at Arnhem, which crosses the Lower Rhine. The objective of the 101st was the Wihelminia Canal bridge at Son, which was blown up by the Germans before the 101st could secure it.

Market-Garden was intended to end the war by December 1944 by allowing Allied troops to cross into the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland. But because of poor planning and difficult terrain, the operation failed to achieve its objectives, leaving Easy Company stranded for almost two months on a 5-kilometer-wide “island” between the Lower Rhine and the Waal River.

“Some of those firefights in Holland were really bad,” recalls Lipton. “The weather was terrible there, rainy. We were in foxholes that were pure mud, and we were very uncomfortable. The Germans had observation from across the Rhine because they had the only high ground – what there was of it – and lots of artillery, and whenever we were out during the day, their artillery came in. The worst thing is to be afraid and not be able to do anything about it. The thought of shellfire can get to you. You can’t fight back. There’s nothing you can do but be there.”

“Some of those firefights in Holland were really bad,” recalls Lipton. “The weather was terrible there, rainy. We were in foxholes that were pure mud, and we were very uncomfortable. The Germans had observation from across the Rhine because they had the only high ground – what there was of it – and lots of artillery, and whenever we were out during the day, their artillery came in. The worst thing is to be afraid and not be able to do anything about it. The thought of shellfire can get to you. You can’t fight back. There’s nothing you can do but be there.”

When the Germans launched their surprise counteroffensive in December 1944, the 101st was called in to hold the line south of Bastogne. Ill-equipped and short on rations, medical supplies, and winter clothing, Easy Company took up position near the village of Foy, where its members suffered for more than a month from the intense cold and incessant German attacks.

The end of one fire fight was the beginning of another. But 101st held. The village of Foy fell to Easy Company, was recaptured by the Germans when Easy Company was put in reserve, and was later reoccupied by the 3rd Battalion of the 506th.

And so it went through late January 1945. The 101st came up against the best the German Army could field. Wehrmacht and SS troops were well clothed, well armed and well fed. They outnumbered the 101st. But the towns of Norville and Rachamps fell in short order. It was, finally, a test of wills. And Carwood Lipton, Easy Company and the 101st prevailed.

Key Was Pride in Unit

How does one endure the horror of war? For Lipton, the answer is simple: pride. “You’re part of a group, an organization,” he says. “You develop an intense pride in yourself and in your unit. And you’re just sure you’re not going to let yourself down or the unit down. You have confidence in the guys around you. You can count on them, and they can count on you.” As for the rigors of incessant combat and the constancy of death, Lipton claims it didn’t take a lot of adjustment.

“We’d been trained for two years and we’d talked about combat and what it would be like, and we had training exercises where they fired right over us,” he says. “As for the dead, the bodies, they don’t bother you at all. Enemy bodies make no impression whatsoever. You just don’t care. They’re the enemy. They’re dead and they aren’t going to fight you anymore.

“And the bodies of your own men don’t affect you for very long. There’s a kind of feeling inside of triumph or accomplishment that I was lucky enough or smart enough or good enough to keep from getting killed. It’s too bad about Joe. He just wasn’t able to make it through.”

Lipton admits, however, that the war changed him profoundly. Before he went into the  Army, he was a loner. Anything he wanted to accomplish he did by himself. He had friends, but he didn’t depend on friends or even think of them as being able to help him. In the Army he was impressed by officers who were able to motivate men and get them in a cohesive organization so they could accomplish feats ever they could not imagine.

Army, he was a loner. Anything he wanted to accomplish he did by himself. He had friends, but he didn’t depend on friends or even think of them as being able to help him. In the Army he was impressed by officers who were able to motivate men and get them in a cohesive organization so they could accomplish feats ever they could not imagine.

“When I came out of the Army,” says Lipton, “I had changed in that way. I’d learned to organize people, enthuse them and get them to give their best. And I’ve continued in that frame of mind for the rest of my life.”

After his discharge, Lipton majored in engineering at Marshall College and went to work for Owens-Illinois Inc. He’s worked and traveled widely throughout the world. His first wife, Jo Anne, died in 1975, and in 1976 he married Marie Hope Mahoney, “a beautiful, intelligent woman who has filled my life.” In 1983, he retired to Southern Pines, the small Southern town he’d discovered while training at Camp Mackall.

Comradeship Remains

And now, 57 years after the end of World War II, there’s an epic motion picture that celebrates the achievements of Easy Company. In June, HBO will fly the surviving members of the unit and their wives to France, where they will be honored guests at the D-Day anniversary première of “Band of Brothers.””Each person lives his own life,” says Lipton, “and it’s not very often that groups of people get together and accomplish something meaningful. I’m not the only one who feels this way. When we have unit reunions, we still have that comradeship. We always will.”

Almost six decades after the events that shaped his life and the history of 20th century, Carwood Lipton can enjoy the privilege – and the honor – of reliving the war he once fought, this time from the comfort of his easy chair.

And he can take particular pride in a scene where Sgt. Lipton remarks to Lt. Speirs, the new commander of Easy Company: “They [Easy Company] are happy to have a good leader again.”

Speirs responds, “From what I’ve heard, they’ve always had one. I’ve been told there was always one man they could count on”. Every day he kept their spirits up, kept the men focused, gave them direction, all the things a good combat leader does”. You don’t have any idea who I’m talking about, do you?”

“No sir,” Lipton replies.

“Hell,” says Speirs, “it was you, first sergeant.”

Article reprinted from the Southern Pines Pilot – 15 January 2001